Two things, as they say, can be true at once: The Fed must normalize interest rates in order to combat inflation, and the government should not allow higher interest rates to harm the very people who are most impacted by high inflation.

Let’s start with the second premise. Jerome Powell, Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, has stated on a number of occasions that while higher unemployment is not the primary objective of raising interest rates, it is an inevitable by-product, with unemployment potentially rising as high as 4.6%.[i] He has also lamented that the impact of high inflation falls heaviest on those who are least able to bear it.[ii] With unemployment currently at 3.7% and a civilian labor force of 166.8 million, 1.5 million people could potentially lose their jobs. It makes no sense to help the people most impacted by inflation by throwing many of them out of work. In fact, there are a number of things the federal government can do to ease inflation without generating higher unemployment. In my post next week, I’ll tackle that subject, along with a discussion of the causes of the recent spike in inflation.

This week I want to focus on the first premise: the Fed must “normalize” interest rates. (Click here for an explanation of how the Fed raises and lowers interest rates.) Last year, “normalizing” interest rates implied raising them, because interest rates were very low, both compared with absolute historical interest rate levels, and with the levels of inflation and economic growth. Going forward, rates may need to stay at these levels, or decline if circumstances warrant. But the notion that interest rates should be kept as low as possible as long as there is no inflation demonstrates a complete misunderstanding of the function of interest rates.

What are “Normal” Interest Rates?

In a normal interest-rate environment, interest rates compensate investors for the risks they take when they put their capital to work. (Click here for an analysis of how interest rates compensate investors.) However, for the past two decades, the Fed has kept interest rates at artificially low levels, such that they have not compensated investors. In fact, for seventeen of the past twenty-one years, real interest rates have been negative – meaning inflation was higher than the level of interest rates, and the rate of interest did not compensate for the loss of purchasing power.

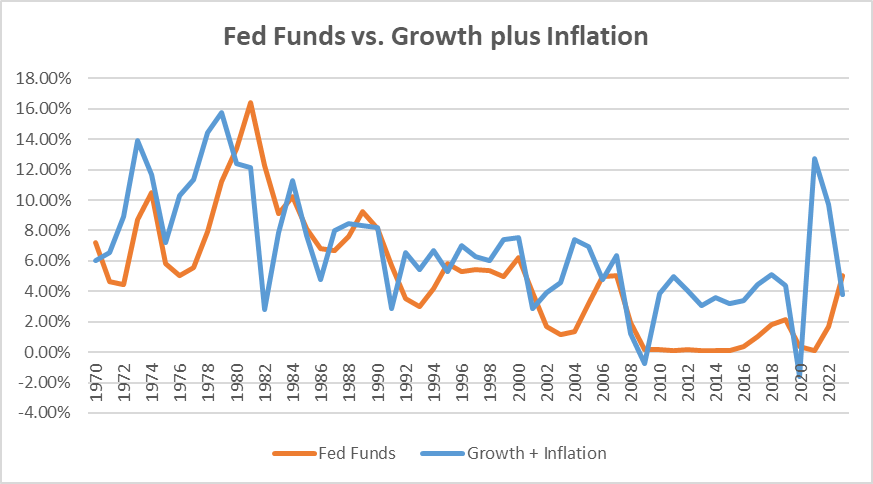

The following chart[iii] depicts the average effective Fed Funds rate[iv] and the level of nominal GDP growth[v] for each year from 1970 through the end of 2022.

From 1970 through 2001, Fed Funds closely tracked nominal GDP; in fact, financial professionals had a widely-shared consensus that the Fed was “neutral” – that is, not trying to use interest rates to affect the economy – when Fed Funds equaled growth plus inflation. The dotcom stock market bust that began in 2000 was accelerated by the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, sending U.S. and global markets into a tailspin. The Fed responded quickly – and appropriately, in my view – to lower interest rates. However, even after the economy began to recover in 2003 and 2004, the Fed kept interest rates artificially low. The Fed raised rates in 2005 and 2006 in response to higher inflation, but in 2008 when the economy was devastated by the Great Recession, the Fed lowered rates to near zero and took other measures to stabilize the financial system. Since 2009, the U.S. has experienced positive real economic growth in every year but one (2020, due to the pandemic), but interest rates have been negative in every year but one (2019).

So, what’s wrong with really low rates? Don’t they stimulate growth? Don’t they allow for higher employment? As long as there’s “no inflation,” aren’t low interest rates an inherently good thing? No, on all counts. Far from being a hindrance to economic growth, interest rates are the fuel of a healthy economy. The ability to earn a return on investment is what drives a capitalist economy, and interest rates are the core of that return. It is excessively low or excessively high interest rates that have a negative impact on the economy. The negative effects of artificially high interest rates are intuitively obvious, but artificially low interest rates are also detrimental.

Low interest rates result in overvalued assets

First of all, artificially low interest rates result in artificially inflated asset prices (stocks, bonds, and real estate, among others). Notwithstanding protestations to the contrary from Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell, we have had inflation for years, just not the type that shows up in the consumer price index. Asset-price inflation can be just as pernicious as consumer price inflation, it just feels good at first. Years of excess liquidity (i.e., low interest rates) resulted in a booming stock market – not because companies were inherently healthy (some were, some weren’t), but because asset prices rise when interest rates fall. (Click here for an analysis of the Components of Expected Return.) The bottom line is this: the value of every investment is the present value of expected future cash flows. When interest rates go down, the value of those cash flows goes up, often creating artificially inflated values.

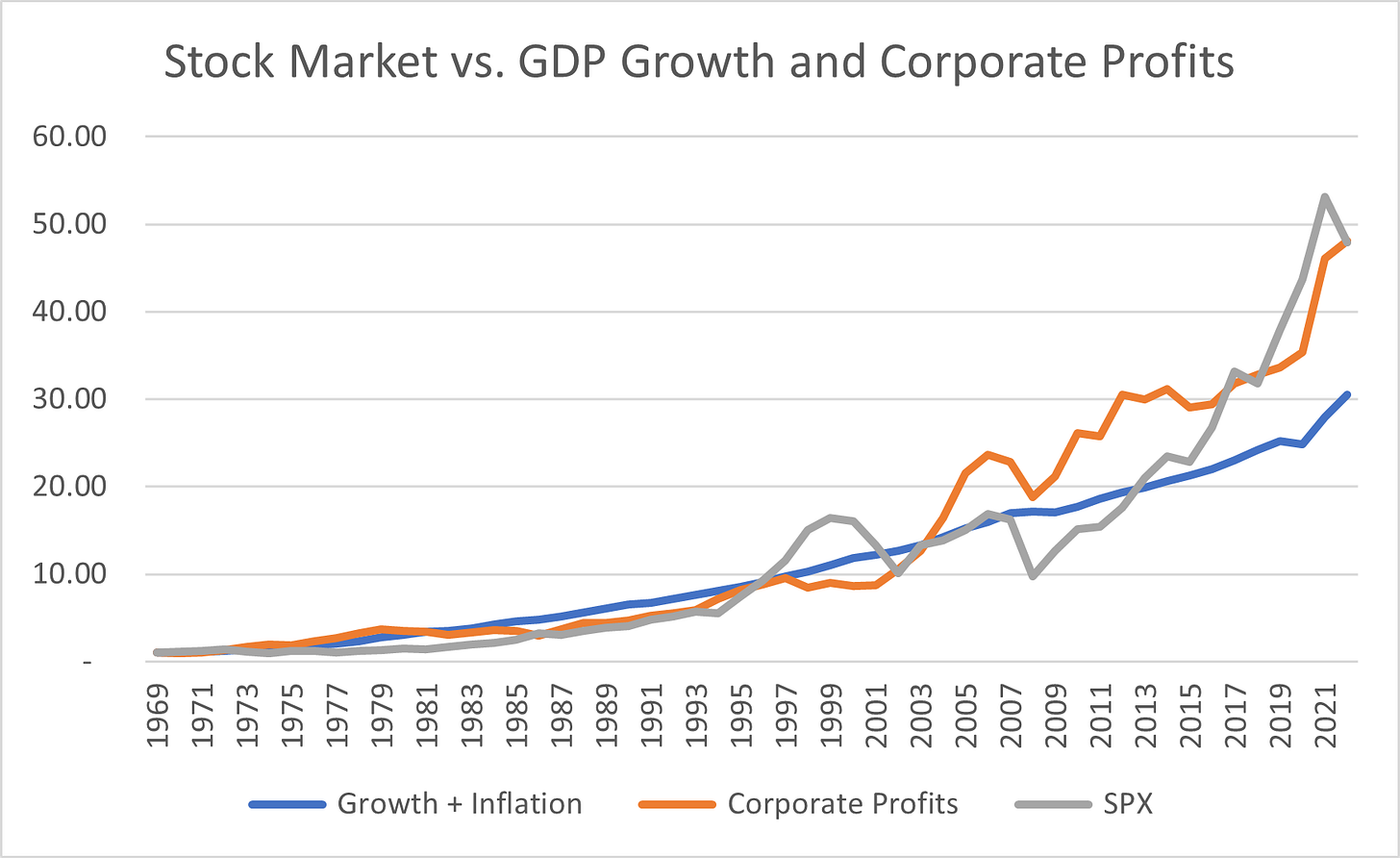

The following chart compares nominal GDP, corporate profits, and stock prices (as measured by the S&P 500).

Until around 2001, corporate profits, nominal GDP and stock prices were closely tied. Stock prices went up because corporate profits rose, and corporate profits rose because the economy was growing. After 2001, with the exception of the 2008 financial crisis, corporate profits rose faster than economic growth, in part because companies were benefiting from the artificially low interest rates. Stock prices also soared, rising faster than corporate profits. From 1970 through 2007, stocks prices rose at a compounded annual rate of 7.6%. Even including the sharp stock market correction in 2022, from 2009 through 2022 the stock market rose at an annual rate of 10.8%.

But rising stock prices are a good thing, right? Well, yes, if they reflect strong growth and healthy corporate profits. Not so much if stock prices are being artificially inflated. Because, just as low interest rates push asset prices higher, rising interest rates will drive asset prices lower. Rising stock values make people feel wealthier, contributing to strong consumer sentiment and spending. Falling stock values have the opposite effect. Even when the economy is healthy, many people – including politicians – tend to equate the well-being of the stock market with the well-being of the economy. In fact, the health of individual companies is closely tied to the health of the economy. But stock prices? Not so much. The stock market often behaves like an overgrown toddler in the candy aisle. Deprive it of the sugary treat of low interest rates, and it will throw itself on the floor in a tantrum. But just like a toddler, it will eventually settle down and eat its broccoli.

Artificially low interest rates can also inflate home values. Until the late 1980s, median home prices generally kept up with inflation. Beginning in 2001, home values began rising more sharply in part because low mortgage interest rates made it possible for people to afford more expensive houses, which in turn drove prices higher. That accelerated following the financial market crisis of 2008 and was even more pronounced in the past two years. (Some of the recent rise in home values was driven by the pandemic, but that’s a subject for another post.)

The problem with home values that have been artificially inflated by low mortgage interest rates is that they become unaffordable when interest rates inevitably rise. And home prices are sticky, meaning they don’t adjust downwards as quickly as they adjust upwards. Once you believe your house is worth nearly half a million dollars (the peak median home price), it’s hard to accept an offer of $320,000, even if it that is what it was worth a few years earlier. Sky-rocketing home values also lead to higher rents, which were a major component of the recent spike in inflation.

The following chart shows the median U.S. home price from 1970 through 2022 and inflation. Through the mid-1980s, home prices tracked inflation. Beginning in 1985 home prices began to rise faster than inflation, and surged after 2008, far outpacing the increase in inflation.

Low interest rates skew business decisions

In addition to inflating asset prices, artificially low interest rates also skew business decisions. When interest rates are artificially low, it’s hard for corporations to make good decisions about where to invest their profits, which is what drives the growth in corporate profits. Businesses weigh the profitability of investment decisions based on their cost of capital, a component of which is the level of interest rates. When the expected return on an investment is higher than the cost of capital, the investment is expected to be profitable. If rates are too low, businesses might green-light investment decisions that would not be profitable in a normal interest rate environment, leading to over-investment. This happened in Asia in the late 1990s. Asian companies invested heavily in export industries, leading to excess supply, and eventually a prolonged recession when the rest of the world could not absorb all their exports.

Low interest rates exacerbate inequality

Perhaps one of the least-appreciated effects of artificially low interest rates is their contribution to wealth inequality. Artificially low interest rates are like a chimney flue, sucking capital upward to those who are already wealthy. The reason is something called “leverage.” Leverage means using borrowed money to make an investment. If your return on the investment is higher than the cost of borrowing, you can make more money than you would if you only invested your own money. But to take advantage of leverage, you need to have your own capital to invest (investors are almost always required to put up some of their own money before they are allowed to borrow), and you need to be eligible for the artificially low interest rates. Most individuals in our society are not eligible, and in fact are usually subject to artificially high interest rates, such as those charged on credit cards. I’ll go into more detail on the causes and consequences of inequality in a future post.

Low interest rates eventually translate into higher inflation

Finally, artificially low interest rates eventually lead to higher inflation. As I mentioned at the beginning, next week I’ll cover the various causes of inflation (only one of which is low interest rates), as well as what the Fed and the federal government can do to restrain inflation, without throwing a lot of people out of work.

The Fed was right to raise interest rates to more normal levels, but they were wrong to keep them artificially low for so long. The question remains whether they have learned their lesson. While the Fed has an important role in managing the nation’s money supply, it is ultimately the market’s job to set interest rates and allocate capital.

[i] AP News: Powell signals increased rate hikes if economy stays strong. https://apnews.com/article/inflation-federal-reserve-interest-rates-powell-unemployment-79b7ead4530ab381a17638a6c9df2d90

[ii] Speech by Jerome Powell at the August 26, 2022 meeting of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/powell20220826a.htm

[iii] Data Sources:

Inflation (CPI-U) – Bureau of Labor Statistics

Fed Funds Rate – St. Louis Fed

GDP Growth - Bureau of Economic Analysis

Corporate Profits – St. Louis Fed

Median Home Prices – St. Louis Fed

S&P 500 – MacroTrends LLC

[iv] The Fed Funds Rate is the rate of interest U.S. banks charge each other to borrow money overnight. This is the rate the Fed targets when it acts to raise and lower interest rates.

[v] Nominal GDP Growth is the dollar value of economic growth. It includes both the increase in production (quantity) and the increase in prices (inflation). In this article I have calculated nominal GDP as real GDP – growth in production net of inflation – plus inflation as measured by the CPI.

This is fantastic! I learned so much and it was very clear and easy to understand. I look forward to future posts

fascinating piece! hadn’t thought about downsides of artificially low rates before. Thanks for laying out so clearly.