Milton Friedman[i] famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it … can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”[ii] What that means in plain English is that inflation can only occur if the money supply is growing faster than economic growth. By implication, it means that only the Fed – with absolute control of the nation’s money supply – can cause an increase or decrease in inflation. (Learn more about how the money supply and the economy grow here.)

This monetarist economic theory ignores some important realities. (See here for a comparison of Keynesian and monetarist economic theory.)

First, inflation is actually a function of demand and supply, not the size of the money supply. When consumers demand more of a good than is available, excess demand will drive the price higher. By the same token, if consumers demand less of a good than is available, excess supply will drive the price lower. (Learn more about demand and supply here.) At the level of the entire economy, inflation occurs when aggregate demand exceeds aggregate supply; that is, overall, people demand more stuff than is available for them to consume. Obviously, they need money to pay for it, so the money supply matters, but it is the catalyst, not the cause.

Second, monetarist theory ignores the role of something called velocity. Velocity of money measures the number of times each dollar is spent in the economy. Economic growth does not occur just because the money supply expands; it requires people to actually engage in economic activity by spending. And while the Fed has absolute control over the money supply, velocity is outside their control. Changes in velocity – both in theory and in practice – will affect the relationship between the money supply and inflation.

The following chart[iii] compares GDP growth, growth in the money supply, and changes in velocity from 1970 through the end of 2022.

Until the late 1980s, velocity was fairly stable, and the relationship between the growth in the money supply and GDP growth was stable. In the mid-1990’s velocity accelerated, and GDP growth outpaced money supply growth. However, around the time of the dotcom bust in the early 2000s, velocity began to plummet and the growth in the money supply outpaced GDP growth. The reasons behind the sustained decrease in velocity are complex (and will be the subject of a future post), but what is clear is that the large increase in the money supply relative to growth left the economy vulnerable to inflation if velocity were to accelerate. And it appears to have accelerated in 2021, coinciding with the increase in inflation.

Finally, while increases and decreases in the money supply can affect the general price level, changes in the prices of specific goods are often caused by events unrelated to the money supply. And if the cause of the price spike is not the expanding money supply, raising interest rates to reduce the money supply may not bring the price down. The more essential the good is – food, shelter, gasoline, etc. – the less demand for the good will be affected by excess money in circulation. In fact, over the past two years, the items whose prices have risen the most are some of the most essential goods, for which there are no readily available substitutes.

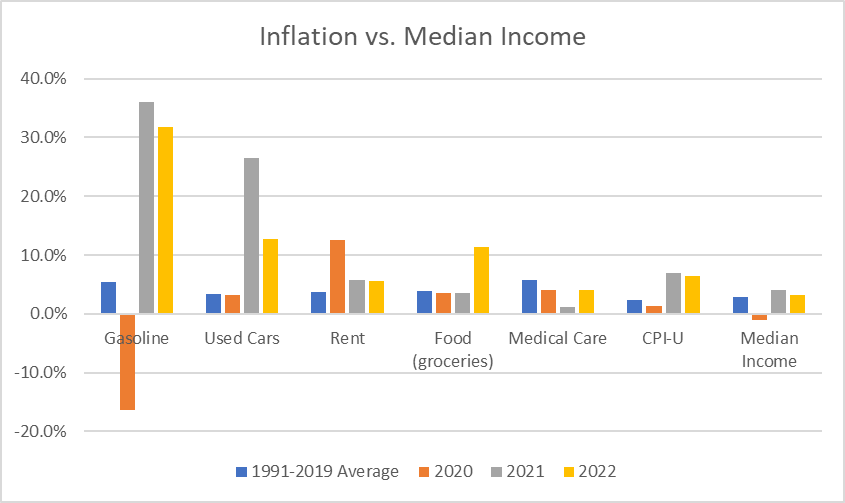

In the following chart[iv] I took select components of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), comparing the historical average annual price increase from 1991 to 2019 with the increases in 2020, 2021 and 2022. Together these five components comprise just over 30% of the CPI. (The BLS website details the components of the CPI). The chart also includes the average annual increase in median income during the same period.

Each item has specific causes for why prices went up, none of which would be remedied by increasing interest rates – absent extreme consequences to the people most affected by inflation. Conversely, each of the causes of higher prices has little to do with the money supply, the solutions for which are in the hands of the federal government, not the Fed.

Gasoline

Average gasoline prices in the U.S. rose from a low of $1.87 per gallon in May 2020 to an all-time high of $4.929 in June 2022. The spike was caused by a number of factors, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine which prompted Western democracies to sanction Russian oil exports. Russia is one of the top three producers of oil (the U.S. is by far the largest producer, while Russian and Saudi Arabia vie for second place). The fear of supply shortages led to a spike in oil prices, which translated into increases in petroleum derivatives such as gasoline. The U.S. government reacted by releasing oil from the strategic oil reserve, but the measure was more symbolic than practical, as the amount of oil released was small relative to global oil consumption.[v] Throughout 2022 Russia managed to find markets for its oil (the largest of which, by the way, is India) and gas prices fell by more than 20% from their peak. However, in April 2023, OPEC[vi] surprised the markets by announcing production cuts, and both oil and gas prices rose. Again, there is nothing higher interest rates in the U.S. would do to alleviate gasoline prices. In fact, there is substantial evidence that the major oil companies used the crisis to increase their profit margins by raising prices more than inflation.[vii] In a future post I’ll explore how corporate profits have risen faster than economic growth.

Used cars

Used car prices rose 26.6% in 2021 and 12.7% in 2022. Although people can put off car purchases in the short-term, eventually cars break down and people need a form of transportation. Substitutes, such as public transportation, are not always feasible alternatives.

Used car prices rose for three reasons. First, global supply chain disruptions during the pandemic created a shortage of microchips needed for new car production. A shortage of new cars led to a shortage of used cars, as rental car companies were unable to replace their fleets and sent fewer cars to the used car market. In 2021, the federal government took action to help alleviate supply chain bottlenecks and passed the CHIPS and Science Act[viii] to promote domestic production of microchips and forestall a similar crisis in the future.

Second, there were fewer car repossessions thanks to pandemic-related stimulus support that helped thousands of consumers stay current on their car payments.[ix] While this support contributed to the shortage of used cars, it is hard to argue that decreased car repossession is bad for society.

Finally, in the face of supply chain shortages, auto makers prioritized production of higher-end cars, making new cars more unaffordable, and prompting used car owners to hang on to their vehicles longer. In March 2023, NPR reported that from December 2017 to December 2022, sales of new cars under $25,000 declined from 13% of total new-vehicle sales to about 4%. Meanwhile, sales of new cars over $60,000 went from 8% to 25% of new vehicle sales.[x] While the Fed can’t address these private-sector business decisions through monetary policy, the federal government could provide incentives for production of more affordable vehicles. That is unlikely to happen, as it appears that the federal government’s desire to promote production of electric vehicles depends on car companies having strong cash flows to fund research and development.

Rent of primary residence

The median asking rent in the U.S. surged in 2020, despite the pandemic, as the nature of housing demand changed with the prevalence of remote work. Rents continued to climb in the following two years as landlords took advantage of generalized inflation to raise rents. The option of buying instead of renting was curtailed by housing prices that had soared thanks to artificially low interest rates. Furthermore, restrictive zoning requirements imposed by cities and municipalities have limited construction of affordable housing in many communities. Finally, low expected returns in stocks and bonds (thanks to artificially low interest rates) drove many large, institutional buyers, such as hedge funds and limited partnerships, to invest in rental properties. Heavy institutional buying resulted in concentrated ownership, which reduces competition among landlords for tenants, and deprives individual renters of the ability to negotiate with multiple potential landlords. A fascinating December 2022 article by Hal Singer[xi] explores the connection between concentration of ownership and rental prices (hint: the correlation is positive) and argues that anti-trust enforcement could help check rental inflation in the long-term. The solution to the housing shortage and high rents is complex, and requires coordination at the federal, state, and local level. What it does not require is higher interest rates that simply exacerbate the problem by making the alternative to renting (buying) more unaffordable.

Food[xii]

Food prices were impacted by a number of disruptions caused by the pandemic. People ate out less, causing shortages at supermarkets. Sick workers caused transportation bottlenecks and shutdowns at food processing plants. The war in Ukraine impacted their exports of agricultural commodities, causing severe shortages in grains and threatening famine in parts of Africa. An outbreak of avian flu sent egg prices skyrocketing. Higher food prices have a significant impact on low-income households, whose food costs comprise around 30% of their income.[xiii] While an expanding money supply may increase demand for higher-end food, the quantity of food consumed is not likely to be affected by the money supply, unless the goal is to get people to eat less than they need.

Medical Care

One category that bucked the inflation trend in 2022 is medical care. As with food, an expanding money supply doesn’t increase the demand for medical care. But the inflation rate of medical care has been coming down, thanks in part to changes in how medical care is delivered following the pandemic (more virtual doctor visits), to measures taken by the federal government to expand subsidies for the Affordable Care Act. That trend is expected to continue as the Inflation Reduction Act allows the federal government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies regarding the price of Medicare drugs. This category underscores the role of the federal government – not the Fed – in combating inflation.

Median Income

If an expanding money supply drives inflation by increasing demand, it would be expected to show up first in rising incomes. People can’t spend more unless they have more money to spend. In fact, since 1991, the median household income barely kept up with inflation, and lagged inflation from 2020 through 2023. In 2020, median household income fell sharply as millions of jobs were lost due to the pandemic. The federal government reacted quickly by providing a total of $814 billion (3.9% of GDP) in stimulus payments,[xiv] which have been blamed for the spike in inflation. Providing people with the wherewithal to buy stuff when that stuff is in short supply due to pandemic-related shortages certainly exacerbated inflation in 2022. But not providing income support would have left millions in poverty, potentially causing a prolonged recession.

Thanks to a strong response from the federal government, unemployment is currently near all-time lows. Historically, tight labor markets tend to give workers more leverage to negotiate wage increases. Wage inflation is one of the Fed’s concerns, hence the need to orchestrate an increase in unemployment.[xv] However, incomes remain essentially flat in real terms, meaning there is not a lot of excess income to drive demand for goods. Additionally, some of the 2021 increase in household income was due to pandemic-related stimulus, which is ending. Thus far, the low unemployment rate hasn’t translated into rapidly growing wages.

Interest rates are now “normal”

My last post discussed the consequences of artificially low interest rates, which can spark asset price inflation that eventually translates into consumer inflation. Interest rates are now in the range that would historically be considered “normal.” The most recent CPI data shows inflation falling in the first quarter of 2023 to a 4.05% annual rate. GDP grew in the first quarter by 1.1%, leaving the “growth plus inflation” calculation at 5.15% - below the current Fed Funds rate of 5.25%

. Although the Fed did not raise rates at its last meeting, it did signal that more rates hikes might be in the cards because inflation remains above their target of 2%. If the Fed continues to raise rates, there is a real risk of recession later this year. The Conference Board[xvi] is predicting a slowdown in the second quarter of 2023 to 0.6%, and negative growth for the three quarters after that. Continued rate hikes would make the most vulnerable pay the price of the Fed’s monetary malpractice over the past few years.

In the final analysis, low interest rates are not the only cause of inflation, and higher interest rates are not the only cure. And while the Fed has an important role in controlling inflation, it has a dual mandate: “The monetary policy goals of the Federal Reserve are to foster economic conditions that achieve both stable prices and maximum sustainable employment”.[xvii] It would compound the damage done by prolonged, artificially low interest rates to continue using the blunt tool of higher interest rates because the Fed only has a hammer and therefore must treat every problem as a nail.

It is time for Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to tell Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen that the Federal Reserve has done its job, and it is now up to the federal and state governments. It is their job to foster conditions that promote long-term, sustainable growth. Ultimately the question we have to ask as a society is whether we want to keep inflation low by keeping people poor, or if we want to grow the economic pie for everyone.

[i] Milton Friedman was the recipient of the 1976 Nobel Memorial Price in Economic Sciences for his research on consumer behavior. He is one of the most famous alumni of the Chicago School, a conservative, monetarist school of economic theory.

[ii] https://www.frbsf.org/our-district/press/presidents-speeches/williams-speeches/2012/july/williams-monetary-policy-money-inflation/

[iii] Sources:

- GDP Growth: Bureau of Economic Analysis

- M2 & Velocity: St. Louis Federal Reserve

[iv] Sources:

- CPI components: Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Median Household Income: Statisa / Census Bureau

[v] The US government released 50 million barrels of oil from the strategic petroleum reserve in November 2021 (https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/11/23/president-biden-announces-release-from-the-strategic-petroleum-reserve-as-part-of-ongoing-efforts-to-lower-prices-and-address-lack-of-supply-around-the-world/), and another 1 million barrels in March 2022 (https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/31/oil-markets-us-strategic-petroleum-reserve.html). Global consumption of crude oil in 2022 was nearly 100 million barrels per day (https://www.statista.com/statistics/271823/global-crude-oil-demand/#:~:text=The%20global%20demand%20for%20crude,barrels%20per%20day%20in%202022).

[vi] The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. See the member countries at this website https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/25.htm

[vii] https://www.epi.org/blog/corporate-profits-have-contributed-disproportionately-to-inflation-how-should-policymakers-respond/

[viii] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/08/09/fact-sheet-chips-and-science-act-will-lower-costs-create-jobs-strengthen-supply-chains-and-counter-china/

[ix] https://www.autoweek.com/news/industry-news/a36863741/used-car-prices-skyrocketing/

[x] https://www.npr.org/2023/03/18/1163278082/car-prices-used-cars-electric-vehicles-pandemic

[xi] https://www.thesling.org/the-rent-is-too-damn-high-and-concentration-may-be-to-blame/

[xii] Food consumed outside the home is excluded from this analysis since people normally have the option of not eating at restaurants.

[xiii] https://www.gao.gov/blog/sticker-shock-grocery-store-inflation-wasnt-only-reason-food-prices-increased#:~:text=While%20food%20prices%20generally%20increased,this%20increase%20the%20same%20way

[xiv] https://www.pandemicoversight.gov/news/articles/update-three-rounds-stimulus-checks-see-how-many-went-out-and-how-much#:~:text=More%20than%20476%20million%20payments,households%20impacted%20by%20the%20pandemic.

[xv] https://rooseveltinstitute.org/2023/02/10/what-does-powell-think-about-wages-now/#:~:text=Throughout%202022%2C%20Federal%20Reserve%20Chair,wage%20growth%20was%20in%20fact

[xvi] https://www.conference-board.org/research/us-forecast

[xvii] https://www.chicagofed.org/research/dual-mandate/dual-mandate